It has been a tragic weekend for the film industry: we lost one of the most talented actors of our generation, Philip Seymour Hoffman, and Dylan Farrow, film director Woody Allen‘s adoptive daughter came out with some harrowing news. I felt compelled to weigh in briefly on these two serious matters.

I will start with Dylan Farrow’s open letter on The New York Times. It received 3,500 comments in the past 48 hours and sparked a lot of controversy. It opens like this:

What’s your favorite Woody Allen movie? Before you answer, you should know: when I was seven years old, Woody Allen took me by the hand and led me into a dim, closet-like attic on the second floor of our house. He told me to lay on my stomach and play with my brother’s electric train set. Then he sexually assaulted me. He talked to me while he did it, whispering that I was a good girl, that this was our secret, promising that we’d go to Paris and I’d be a star in his movies. I remember staring at that toy train, focusing on it as it traveled in its circle around the attic. To this day, I find it difficult to look at toy trains.

For as long as I could remember, my father had been doing things to me that I didn’t like. I didn’t like how often he would take me away from my mom, siblings and friends to be alone with him. I didn’t like it when he would stick his thumb in my mouth. I didn’t like it when I had to get in bed with him under the sheets when he was in his underwear. I didn’t like it when he would place his head in my naked lap and breathe in and breathe out. I would hide under beds or lock myself in the bathroom to avoid these encounters, but he always found me. These things happened so often, so routinely, so skillfully hidden from a mother that would have protected me had she known, that I thought it was normal. I thought this was how fathers doted on their daughters. But what he did to me in the attic felt different. I couldn’t keep the secret anymore.

When I asked my mother if her dad did to her what Woody Allen did to me, I honestly did not know the answer. I also didn’t know the firestorm it would trigger. I didn’t know that my father would use his sexual relationship with my sister to cover up the abuse he inflicted on me. I didn’t know that he would accuse my mother of planting the abuse in my head and call her a liar for defending me. I didn’t know that I would be made to recount my story over and over again, to doctor after doctor, pushed to see if I’d admit I was lying as part of a legal battle I couldn’t possibly understand. At one point, my mother sat me down and told me that I wouldn’t be in trouble if I was lying – that I could take it all back. I couldn’t. It was all true. But sexual abuse claims against the powerful stall more easily. There were experts willing to attack my credibility. There were doctors willing to gaslight an abused child.

After a custody hearing denied my father visitation rights, my mother declined to pursue criminal charges, despite findings of probable cause by the State of Connecticut – due to, in the words of the prosecutor, the fragility of the “child victim.” Woody Allen was never convicted of any crime. That he got away with what he did to me haunted me as I grew up. I was stricken with guilt that I had allowed him to be near other little girls. I was terrified of being touched by men. I developed an eating disorder. I began cutting myself. That torment was made worse by Hollywood. All but a precious few (my heroes) turned a blind eye. Most found it easier to accept the ambiguity, to say, “who can say what happened,” to pretend that nothing was wrong. Actors praised him at awards shows. Networks put him on TV. Critics put him in magazines. Each time I saw my abuser’s face – on a poster, on a t-shirt, on television – I could only hide my panic until I found a place to be alone and fall apart.

Last week, Woody Allen was nominated for his latest Oscar. But this time, I refuse to fall apart. For so long, Woody Allen’s acceptance silenced me. It felt like a personal rebuke, like the awards and accolades were a way to tell me to shut up and go away. But the survivors of sexual abuse who have reached out to me – to support me and to share their fears of coming forward, of being called a liar, of being told their memories aren’t their memories – have given me a reason to not be silent, if only so others know that they don’t have to be silent either…

To read the full letter, please visit: http://kristof.blogs.nytimes.com/2014/02/01/an-open-letter-from-dylan-farrow/

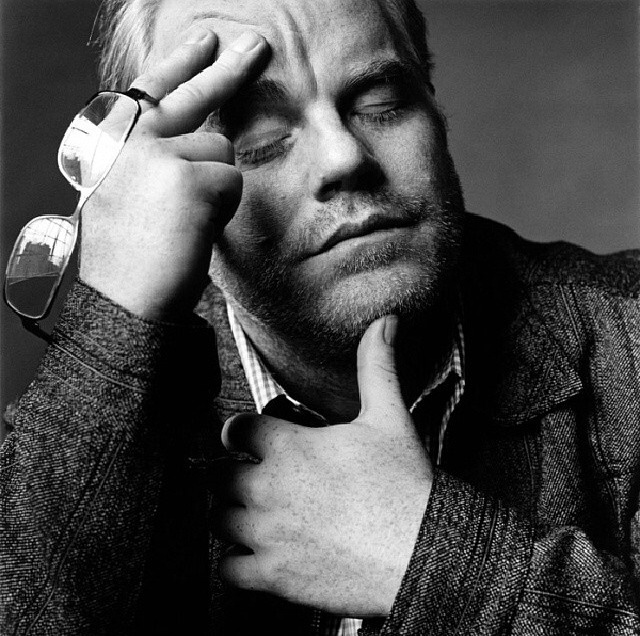

And then, just yesterday, as football fans everywhere prepared to cheer on their favorite Superbowl team, the headlines started to pop up: Philip Seymour Hoffman, 46, Found Dead in his New York City Apartment From Alleged Heroin Overdose. Syringe Found Still In His Left Arm.

I know all too well about the horrific disease of addiction. I have an uncle who struggles and I also lost a cousin, a brilliant surgeon to drug addiction.

Today, I chose not to comment on either of the above (only voicing that I believe wholeheartedly in Dylan’s accusation), because I don’t know the intricate details of either case any more than you do.

But here is what I do know. It always, unfortunately, takes a significant loss to start a conversation– whether it’s a high school shooting to prompt more rigid gun laws, or a mother killing her children to spark the mental illness / healthcare debate. It usually takes a significant loss to begin a dialogue. But in these conversations, something happens. In these uncomfortable conversations, we begin to release the stigma. We begin to release the shame. In the two cases above… the stigma of drug addiction, as well as sexual abuse.

So I ask you today: What will it take to make us open up about these issues? Because where there is stigma attached, we stay hidden in the closet and we suffer quietly. We certainly don’t publicize THAT on Instagram.

The conversation begins with us. With you, and with me.

Who would like to start?

Thank you for this post. I completely agree with you. RIP Phillip Seymour Hoffman.

Well said Erica. Addiction in Hollywood is so rampant and I don’t know why but I agree that we need to remove the shame so that people aren’t embarrassed to seek help.

I feel awful for his family and friends. He had a serious addiction . He was a sick selfish man.

Many sick people die every day with no choices. He had many. His disease was cure able as many ARE NOT!

As far as woody goes, where there is smoke, there is fire.